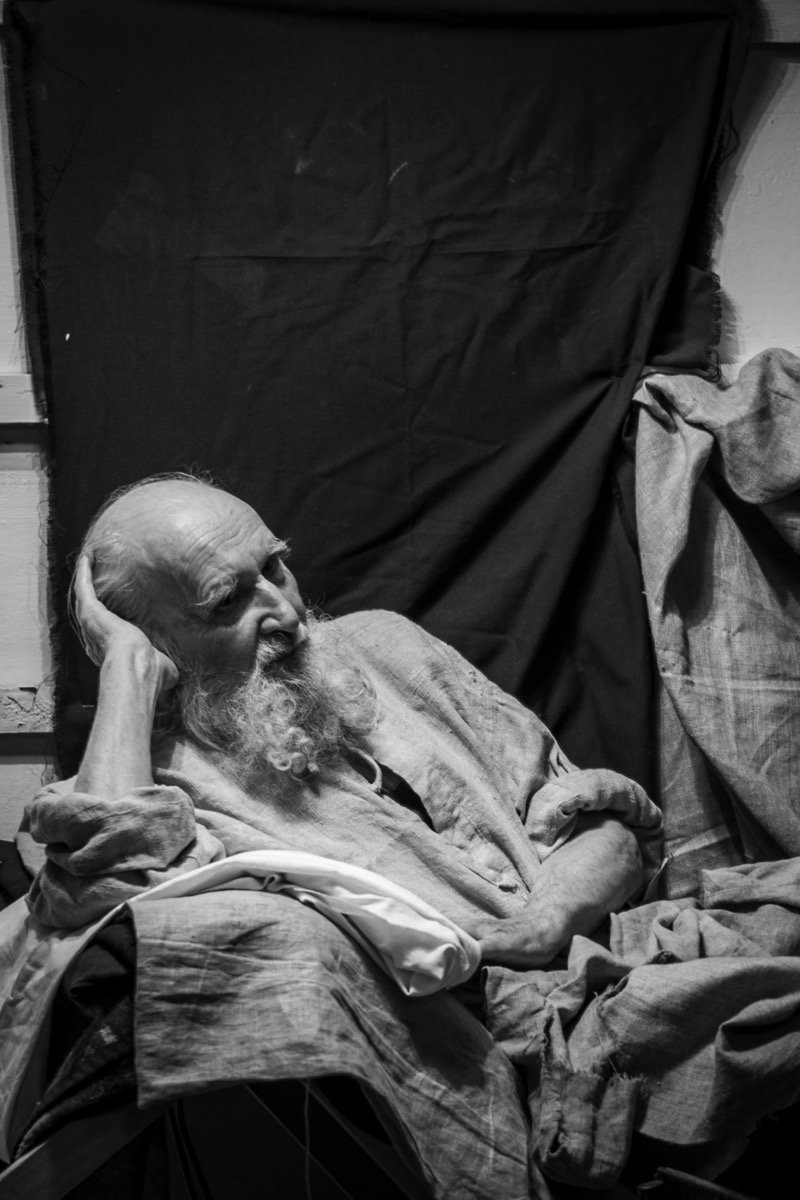

“The landscape of the Russian soul corresponds with the landscape of Russia, the same boundlessness, formlessness, reaching out into infinity.”

Nikolai Berdyaev (1874-1948)

It is said that the term “Russian soul” first appeared in the writings of the literary critic, Vissarion Belinskii, upon the publication of Nikolai Gogol’s masterpiece Dead Souls in 1842, the novel describing the chief protagonist’s scheme of purchasing claims to deceased serfs for accounting purposes. However, the expression is perhaps more familiar to the Western reader in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot where we read in English translation the frequently-quoted phrase “The Russian soul is a dark place”. In fact, this is a misrepresentation of the original text, русская душа потемкиl, which is more accurately translated “The Russian soul is a mystery”, the emphasis being on the mysteriousness or impenetrability of the Russian soul, rather than anything inherently dark or sinister. Nowhere is this mystery more palpable than for a visitor who steps inside a Russian Orthodox Church for the first time: the soft light illuminating the iconostasis, the deep baritone voices of the chanted liturgy, the devout congregation standing in clusters before their revered icons, couples silently waiting in line to be blessed by the priest. Every impression conspires to evoke a sense of mystery, of that other worldliness that symbolizes man’s connection to the divine.